Victims of spyware and a group of security experts have privately warned that a European parliament investigatory committee risks being thrown off course by an alleged “disinformation campaign”.

The warning, contained in a letter to MEPs signed by the victims, academics and some of the world’s most renowned surveillance experts, followed news last week that two individuals accused of trying to discredit widely accepted evidence in spyware cases in Spain had been invited to appear before the committee investigating abuse of hacking software.

“The invitation to these individuals would impede the committee’s goal of fact-finding and accountability and will discourage victims from testifying before the committee in the future,” the letter said.

It was signed by two people who have previously been targeted multiple times by governments using Pegasus: Carine Kanimba, the daughter of Paul Rusesabagina, who is in prison in Rwanda, and the Hungarian journalist Szabolcs Panyi. Other signatories included Access Now, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Red en Defensa de los Derechos Digitales, and the Human Rights Foundation.

One MEP said it appeared that Spain’s “national interest” was influencing the committee’s inquiry.

The invitation to one of the individuals – José Javier Olivas, a political scientist from Spain’s Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia – was rescinded but the other, to Gregorio Martín from the University of Valencia, was not and he is expected to appear before the parliamentary panel on Tuesday.

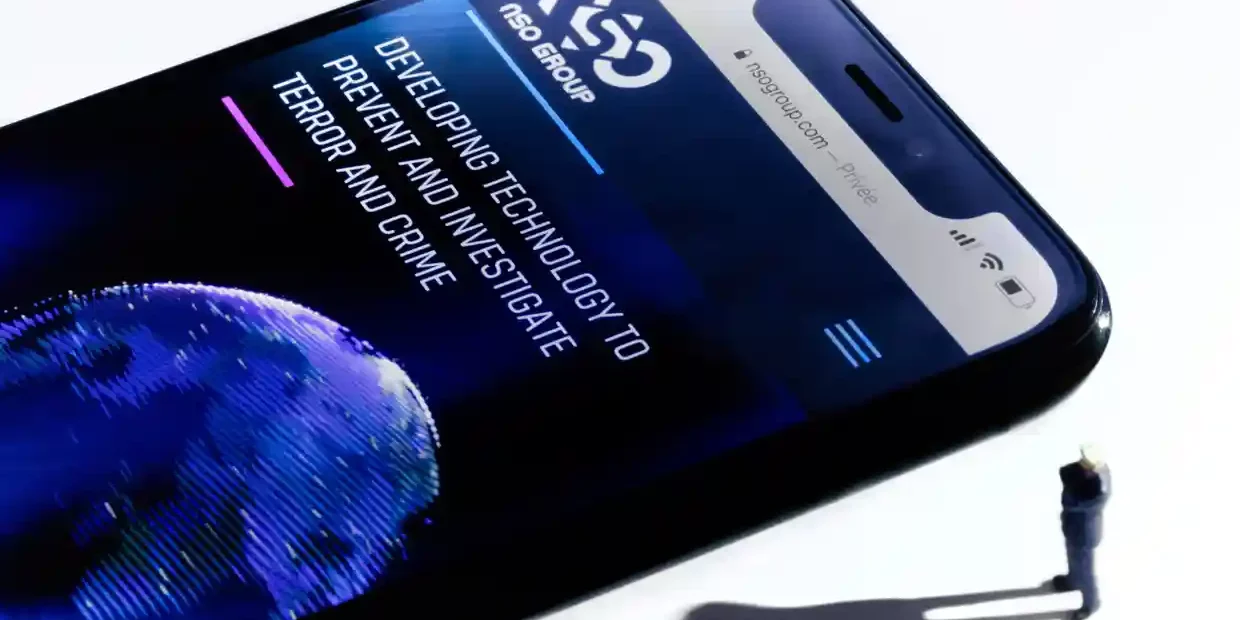

At the centre of the controversy lies the European parliament’s committee investigating the use of Pegasus, a powerful surveillance tool used by governments around the world. Pegasus is made and licensed by NSO Group, an Israeli company that was blacklisted by the Biden administration last year, after the US said it had evidence that foreign governments had used its spyware to maliciously target government officials, journalists, businesspeople, activists, academics and embassy workers.

Researchers at Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto and Amnesty International’s Security Lab have documented its use in countries including Spain, Poland and Hungary.

While their findings have been used and accepted as evidence in courts in the UK and the US, they have come under sustained attack in recent months by a small but vocal group of individuals who have sought to question the researchers’ conclusions in ways dismissed as unfounded and conspiratorial by security experts.

The letter accuses Olivas of engaging in a pattern of harassment against researchers, including by “promoting conspiracy theories and false claims about researchers”, victims and institutions in more than 500 posts on Twitter.

Olivas told the Guardian he rejected the accusations and had requested a formal explanation from the committee about his rescinded invitation. He also said he had complained to the president of the European parliament.

“I believe that this case can be illustrative of the risk of instrumentalisation of a committee of inquiry by third parties with vested interests. It sets a dangerous precedent. Giving in to pressures from third parties to filter evidence before a hearing goes against the principles of any serious investigation,” he said. He said he did not have any relationship with the current or previous Spanish governments.

Martín was invited as a “peer reviewer” on a research paper experts said had frequently been promoted even though – the letter alleged – it contained basic technical errors and false statements about some Pegasus victims.

Martín said in an email to the Guardian he had been “hurt” by the letter seeking to disqualify him but that he was busy preparing his testimony and trying to be “as positive as possible”. He declined to respond to specific allegations raised in the letter.

“I definitely think there is a national influence on the work of the inquiry committee,” said Saskia Bricmont, a Belgian MEP and member of the Greens/European Free Alliance group. “Spain is showing its national interest, but not just Spain.”

Two people close to the parliamentary committee said it was not entirely clear why Olivas and Martín had been invited, but that they believed their names had been put on a preliminary agenda by Spanish members of the centre-right European People’s party (EPP) group.

Juan Ignacio Zoido Álvarez, Spain’s interior minister from 2016-18 at the height of the Catalan independence crisis and now the EPP’s coordinator on the committee, declined to comment. An assistant to the MEP said he did not wish to interfere with the internal processes but that he would comment after Tuesday’s hearing.

Revelations about the use of the spyware in Spain – both against Catalan independence figures and central government ministers – have proliferated over recent years, prompting concerns over a lack of oversight and security and culminating in the dismissal six months ago of the country’s spy chief.

In June 2020, the Guardian and El País reported that at least three senior pro-independence Catalan politicians had been told their phones had been targeted using Pegasus.

At the time, the Spanish government vehemently denied targeting the Catalan independence movement, saying: “This government doesn’t spy on its political opponents.” The National Intelligence Centre (CNI), however, gave a more guarded answer, saying its work was overseen by Spain’s supreme court and it always acted “in full accordance with the legal system, and with absolute respect for the applicable laws”.

A report this year from Citizen Lab alleged at least 63 people connected with the Catalan independence movement – including the current regional president, Pere Aragonès – were targeted or infected with Pegasus. The report said lawyers, journalists and civil society activists were also targeted, and that almost all the incidents took place between 2017 and 2020.

It also emerged that the phones of three of Spain’s most senior politicians – the prime minister, Pedro Sánchez, the defence minister, Margarita Robles, and the interior minister, Fernando Grande-Marlaska – were in 2021 subjected to “illicit” and “external” targeting using Pegasus.

Paz Esteban, the head of the CNI, reportedly confirmed to a congressional committee that the centre had spied on 18 members of the Catalan independence movement, including Aragonès, with judicial approval. She was sacked shortly afterwards.

Ron Deibert, the founder and head of the Citizen Lab, said in a statement to the Guardian that the committee’s work was “crucial to shed light on abuses around the mercenary spyware market”.

He added: “We respect the committee and its critical mission. Culpable governments, and their allies, may have a vested interest in ensuring those proceedings do not succeed. That is why it is so essential that the expert witnesses called to testify be uniformly credible. Unfortunately, that does not appear to be the case for this hearing.”

The Spanish government did not respond to requests for comment.